In order for the kidneys to function, blood is pumped through the aorta which supplies the paired renal arteries. Each artery branches multiple times until it reaches the functional unit of the kidney, the glomerulus. Blood flows into the glomerulus via the afferent arteriole and out via the efferent (e for exiting) arteriole. These arterioles are controlled by a hormonal regulation system that helps control how much blood flow and pressure each glomerulus sees.

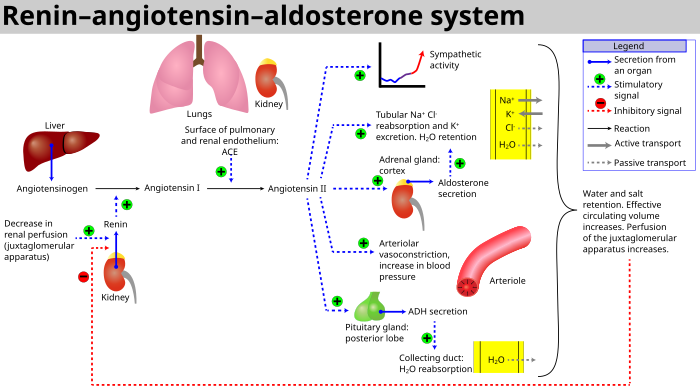

The hormonal pathway is called the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAS) system. When renal blood flow (RBF) is reduced, cells near the glomerulus called the juxtaglomerular apparatus convert circulating prorenin into renin. Renin catalyzes the conversion of liver-produced angiotensinogen into angiotensin I. This in turn is a precursor for angiotensin II. The conversion is facilitated by angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) found on the surface vascular endothelial cells, primarily in the lungs.

Angiotensin II has several functions. First, it causes vasoconstriction, primarily at the efferent arteriole. It also stimulates secretion of aldosterone from the adrenal gland, which helps sodium reabsorption and potassium excretion. It also facilitates antidiuretic hormone secretion from the pituitary gland. Generally, angiotensin II wants to preserve circulating volume and blood flow.

|

| RAAS Schematic Source: Wikipedia |

In normal physiology, renal blood flow (RBF) and glomerular filtration rate are maintained in a narrow range, regardless of blood pressure. Too much RAS activation though can lead to hypertension. Many medications affect particular steps in this pathway to disrupt that activation.

ACE Inhibitors (ACE-i) function by blocking the angiotensin converting enzyme, decreasing the formation of angiotensin II (A-II). This can maintain renal function by decreased vasoconstriction and decreased sodium retention, while increasing renal blood flow. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) may stay the same or even decrease, due to the differential effects on the afferent and efferent arterioles. Since A-II increases GFR by constricting the efferent arteriole relatively more, blocking A-II will dilate the efferent arteriole to a greater degree. The result is more blood flowing through the kidney overall, but less of it actually being filtered by the glomerulus.

This effect on the kidney is reflected in an expected slight rise in creatinine after initiating ACE inhibitor therapy. The expected rise is usually between 10 and 20%. Acute kidney insufficiency (AKI) is defined as a rise greater than 0.5 if the serum creatinine was initially less than 2.0 mg/dL or more than 1.0 if the baseline was greater than 2. AKI is exacerbated in patients with congestive heart failure (CHF), and can occur even years after therapy was started.

Four mechanisms have been proposed for how ACE-i cause AKI in this setting. The main mechanism occurs if ACE-i cause the mean arterial pressure to decrease to a point that renal perfusion cannot be maintained. The other causes include: simultaneous diuretic use, NSAID use, or high grade renal artery stenosis.

Presuming the latter three causes have been excluded, ACE inhibitor-induced AKI can be managed with close monitoring of serum creatinine and potassium levels. Hyperkalemia is also common, as blocking A-II causes potassium to accumulate in the circulation. This is exacerbated in patients with diabetes, hyperglycemia, and on beta-blockers (which are common in CHF patients). Once adequately titrated, ACE-i therapy can continue as most induced AKI is reversible and potassium levels can be managed by reducing other potassium-retaining interventions. The long-term benefits of ACE-i should outweigh these short-term issues.